When it comes to food and beverage products, how good it tastes is essential for its success. However, this is just the starting point. How the product is presented to the market is also critical to its success and businesses make significant investments, both financially and in time and effort, to ensure their product catches the consumer’s eye.

The shape of the product (think of the iconic McCains potato smiles), the use of a distinctive colour (like Cadbury’s signature purple), or the adoption of a unique aspect of packaging may be intrinsically associated with the product for consumers and act as a badge of origin distinguishing it from other similar products in the market. Despite the value that non-traditional trade marks, such as shape, colour, sound, scent or aspects of packaging may have, these branding elements are often overlooked by businesses when considering obtaining registrable intellectual property rights.

The Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) defines a trade mark as a ‘sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person”[1].

The term ‘sign’ is further defined in the Act to include “any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent” or any combination of them. [2]

In light of this broad definition, businesses in the food and beverage industry should consider whether they have adequate protection for all intellectual property associated with their products and whether obtaining trade mark registration for a non-traditional trade mark would foster greater brand protection and preserve the intended competitive advantage that it was intended to create.

The most common forms of non-traditional trade marks in the food and beverage industry, being shape marks and colour marks, are discussed below.

Shape marks

Most food and beverage products are designed to be shaped or packaged in a manner that is commonplace to the relevant industry. For example, wine is ordinarily sold in a long, glass bottle with an extended tapered neck and therefore wine offered for sale in the marketplace in a standard, industry-approved bottle is generally not distinguishable from other competitors’ products by its shape.

However, the three-dimensional shape of a product may function as a trade mark if it is not a shape other traders are likely to wish to use for the same or a similar product in the ordinary course of their business. It is important to consider whether the shape of the product has a significant functional feature, such as:

- being essential to the use or purpose of the article;

- being needed to achieve a particular technical result;

- having an engineering advantage which results in improved performance; or

- resulting from a comparatively simple and cost-effective manufacturing method[3].

If the product’s shape is for a functional purpose, it could be difficult to establish that other traders are not likely to wish to use that shape without improper purpose and therefore trade mark registration is not likely to be available, unless you can demonstrate acquired distinctiveness through extensive use.

The same considerations apply to the shape or configuration of the packaging of goods.

Colour and Aspects of Packaging

A colour, by itself or in combination with other colours and/or aspects of packaging, may act as a trade mark if, when taken as a whole, it distinguishes the goods or services of one trader from the same or similar goods or services of another trader. Like shape marks, you should ask whether other traders are likely to want to use the colour or colour combination having regard to what is commonly used in the relevant trade or market. Relevant factors to be considered include whether the colour or colour combination:

- it is the natural colour of the goods, for example, as a result of the usual manufacturing process;

- may be regarded as functional;

- serves to provide a particular technical result for the goods concerned; or

- conveys a generally-accepted meaning in the trade or the wider community[4]

If any of these factors apply, it may be difficult to obtain trade mark registration for the colour, colour combination or other aspect of packaging and therefore an enforceable monopoly in respect of it.

Registrations for non-traditional trade marks in the food and beverage industry

Some examples of non-traditional trade marks used in the food and beverage industry that have been successfully registered include:

The iconic packaging associated with ‘Vegemite’ is the subject of a registered Australian trade mark, which contains the following endorsement:

“The Trade Mark consists of the shape of a jar and lid, with the jar bearing a yellow-coloured label including a red-coloured logo, the lid being yellow-coloured and the jar having a contrasting brown colour, as shown in the representation(s) attached to the application form.”

(Australian Registered Trade Mark No 1842067)

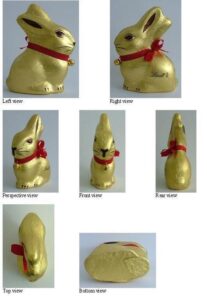

- The manufacturer of the well-known ‘Lindt’ bunny chocolate product, Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprungli AG, recognised the shape, colour and other aspects of packaging of its product acted as a ‘badge of origin’ independent of other prominent logos or markings and obtained the following trade mark registration:

(Australian Registered Trade Mark No. 1164439)

The endorsement to this registration describes the trade mark in the following terms:

“The trade mark consists of the 3-dimensional shape of a rabbit covered by GOLD packaging, a RED ribbon and GOLD bell around the neck of the rabbit, the word LINDT and a device element, as shown in the representations attached to the application form”.

Although non-traditional trade marks may form valuable intellectual property assets of a business, they can be difficult to register. To demonstrate acquired distinctiveness, extensive evidence of use is often required to obtain registration. Rights of this kind may also be difficult to enforce, as illustrated by the recent Federal Court decision of Koninklijke Douwe Egberts BV v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1277 (7 November 2024), which concerned the shape of the ‘Moccona’ instant coffee jar.

Koninklijke Douwe Egberts was the owner of Australian Trade Mark Registration No. 1599824 for the following shape mark:

In or about August 2022, Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd, which is the owner of various registered Australian trade marks containing or comprising the word ‘Vittoria’ in relation to coffee and a range of other similar and related goods and services, began selling its instant coffee under the ‘Vittoria’ brand packaged in a cylindrical glass jar (as displayed below):

The Moccona coffee jar The Vittoria coffee jar

The Moccona coffee jar The Vittoria coffee jar

Koninklijke Douwe Egberts sought relief against Cantarella for infringing their registered shape mark and Cantarella filed a cross-claim seeking cancellation of the registration for the shape of the ‘Moccona’ instant coffee jar, under Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), arguing the shape of the jar was not sufficiently adapted to distinguish it from similar goods of other traders.

Ultimately, the ‘Vittoria’ coffee jar used by Cantarella was held by the Federal Court not to have been used ‘as a trade mark’, with Wheelan J observing:

- The “relatively plain”[5] shape of the coffee jar made it less likely to have the ability to distinguish Canterella’s coffee products from those of other traders; and

- The advertisement of Cantarella’s ‘Vittoria’ coffee product did not attempt to specifically draw the consumer’s attention to the shape of the jar, which itself was heavily branded with the registered ‘Vittoria’ logo and brand name[6].

In relation to Cantarella’s cross-claim seeking cancellation of the registration for the shape of the Moccona coffee jar, the Court considered evidence of how the ‘Moccona’ coffee jar was marketed over an extensive period of time, as well as the lack of other traders selling coffee in a similar jar shape. His Honour also noted the ‘Moccona’ jar had, on occasions, been promoted and advertised without the ‘Moccona’ label and with complete emphasis on the shape of the jar itself[7]. Therefore, the shape mark was held to be registrable and valid, despite containing some functional aspects.

Although this decision illustrates the difficulty in enforcing non-traditional trade marks due to the requirement that the infringing shape, colour and/or aspects of packaging is being used as a badge of origin, the deterrent effect of trade mark registration should also be considered.

A few key takeaways:

- As a starting point, the primary focus should generally be on securing trade mark registration for a word mark and/or associated logo used to identify the trade source of your product.

- When designing your product/packaging, think about how other brands would usually present or package their similar products and whether you intend this feature to set your product apart from competitor products. For example, think about the shapes and colours commonly used in the industry and whether other traders may wish to use the proposed shape or colour for a functional purpose. It is also important to conduct clearance searches to see whether the same or a similar shape or colour is already trade marked for particular goods.

- If the shape of your product or packaging, the particular colour or colour combination used or other aspects of packaging is something you consider valuable to your brand and sets your product apart from others, then you should consider seeking trade mark registration for a non-traditional trade mark.

- If you wish to obtain trade mark registration for a shape mark or colour mark, it is useful to clearly document this in your initial design concepts and emphasise and promote its unique shape or colour as part of the subsequent advertising campaign, to develop strong brand recognition in that element independent of the associated brand name.

Despite the challenges in securing registration for non-traditional trade marks, such as shape and/or colour and/or other aspects of packaging, and then enforcing those rights, obtaining trade mark registration may still be an important step in preserving the competitive advantage created by a product’s distinctive presentation.

Our team has extensive expertise in securing and enforcing intellectual property rights in the food and beverage industry and would welcome the opportunity to discuss securing trade mark registration for a non-traditional trade mark, including a shape or colour trade mark, with you.

[1] Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), section 17.

[2] Ibid, section 6.

[3] IP Australia, Trade Marks Manual of Practice and Procedure, Section 21. 3 ‘Shape (three dimensional) trade marks’ <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/trademark/3.-shape-three-dimensional-trade-marks>

[4] IP Australia, Trade Marks Manual of Practice and Procedure, 21.4 ‘Colour and coloured trade marks’, <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/trademark/4.-colour-and-coloured-trade-marks>

[5] Koninklijke Douwe Egberts BV v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1277 (7 November 2024) [460].

[6] Ibid, [463].

[7] Ibid, [53], [77], [83] and [512].